The City Wakes, The City Sleeps – Curator Interview

John Brack, Subdivision 1954, TarraWarra Museum of Art Collection. Purchased 2004

Information for Students and Teachers

Explore the exhibition through conversations with the curators, James Lynch and Dr Victoria Lynn, Director, TarraWarra Museum of Art.

What are your collaborative responsibilities in curating this exhibition?

TarraWarra Museum of Art Director Dr Victoria Lynn led a team including James Lynch as Curator and Emma Nixon as Assistant Curator to jointly curate this exhibition. Belinda Cameron, Registrar and Collections Manager, also provided input and advice about the safe care and movement of specific artworks. Charlotte Carter, Exhibitions Manager, was responsible for managing the installation of the exhibition, organising a team of artwork specialist handlers, builders, painters and lighting technicians. Exhibitions are always a big team effort and everyone who works at TarraWarra has a professional attitude to working as part of a team. We work in unison, respecting the voice and ideas of others and with a practical attitude.

Robert Jacks, The City Sleeps 2006. TarraWarra Museum of Art Collection. Purchased 2007. @ The Estate of Robert Jacks

How did you decide upon the title and themes for this exhibition?

The title of the exhibition was inspired by an abstract painting by Robert Jacks. Entitled The City Sleeps (2006), this large, luminous landscape-shaped oil on canvas evokes a dense cityscape viewed from above. The painting served as one of the key inspirations for both our exhibition concept and its title. Jacks’ work was instrumental in shaping our exploration of the rhythms and poetry of daily life in the modern city. From there we noted that many of the works in our collection depict the modern city during both daylight hours and at night–time. Working through the collection, we developed several themes, which we have called ‘scenes’ in our working method.

These scenes are contextualised by a major First Nations’ work in our collection by Peta Clancy (Yorta Yorta). Entitled Birrarung ba brungergalk the installation depicts the local Birrarung through a First Nations lens. Originally commissioned by the Museum for The Soils Project in 2023, this work explores the confluence where brungergalk (Watts River) meets the birrarung (Yarra River) near Healesville on Wurundjeri Country. brungergalk had been tapped and dammed, without consideration for its vital connection to Country, and its sacred and sustainable value for First Nations communities. Its inclusion in this exhibition signals to visitors the natural and cultural significance of the terrain before the growth of cities.

After visitors experience Peta Clancy’s work, our scenes of the modern city begin: The Modern City, Suburbia, Thresholds, Dynamic Rhythms, The Industrial City, Interior Lives, Dreams and Play.

Peta Clancy, birrarung ba brungergalk 2023, installation view, The Soils Project, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2023. Thank you to Wurundjeri Traditional Custodians for their permissions to photograph their Country. Courtesy of the artist and Dominik Mersch Gallery, Sydney. Photo: Andrew Curtis

What were your curatorial considerations in selecting artworks for this exhibition? What were some of the processes behind these decisions?

TarraWarra Museum of Art Collection is known for its significant holdings of landscape paintings by some of Australia’s leading artists including Sidney Nolan, William Robinson and Mandy Martin. This group of paintings has been featured in our exhibitions prominently over the years. Less known are several artworks that feature life in our urban environments, including the city and surrounding suburbs. We worked as a team with a larger group of around 100 artworks and edited them down by about 50%. We grouped the works under headings or themes reflecting different aspects of urban experience, and in this way the exhibition was divided into different chapters and can tell a story.

What considerations have influenced the relationships and placement between artworks in the exhibition?

Following these steps were considerations around groups of artworks with related subject matter and how they might work together. Artworks from certain times in history were sometimes grouped together, while others were grouped by artist, making these smaller groupings a bit more congruent. In other situations, artists and their works were grouped across different periods of art, to suggest an ongoing set of themes throughout the decades. From there, we printed out all the artworks on paper as thumbnails and pinned them to a large map of the museum on the wall. They then sat for a while like this on the wall and some small adjustments were made.

How did you make decisions about the way the exhibition is laid out? Did any of the artworks’ cultural, materials, size or installation needs influence the placement or inclusion of these works in this exhibition?

The process of creating the exhibition design begins with a manual sketch on the floor plan. The Assistant Curator then worked with the curators, producing several versions using Adobe InDesign. We have mock-ups of each wall in the museum drawn to scale. Images of each artwork was imported into the program matching the scale and then artworks were laid out so we could have a better idea how things would fit, and we filled the walls with colour to help with the exhibition design. It is always the case that when we are in the space with the artworks, some get moved around to create more meaningful relationships and further connections.

What methods and considerations have been implemented in creating didactics about the themes, artists and artworks in this exhibition?

We grouped the exhibition into themes around Country, the modern city, suburbia, industry, interiors, rhythms, dreams and play. As curators we relish the opportunity to write about art and life in this way. We value giving audiences accessible entry points to thinking about the artists, the artworks and their own experiences.

What themes and ideas addressed in this exhibition communicate with contemporary culture and society?

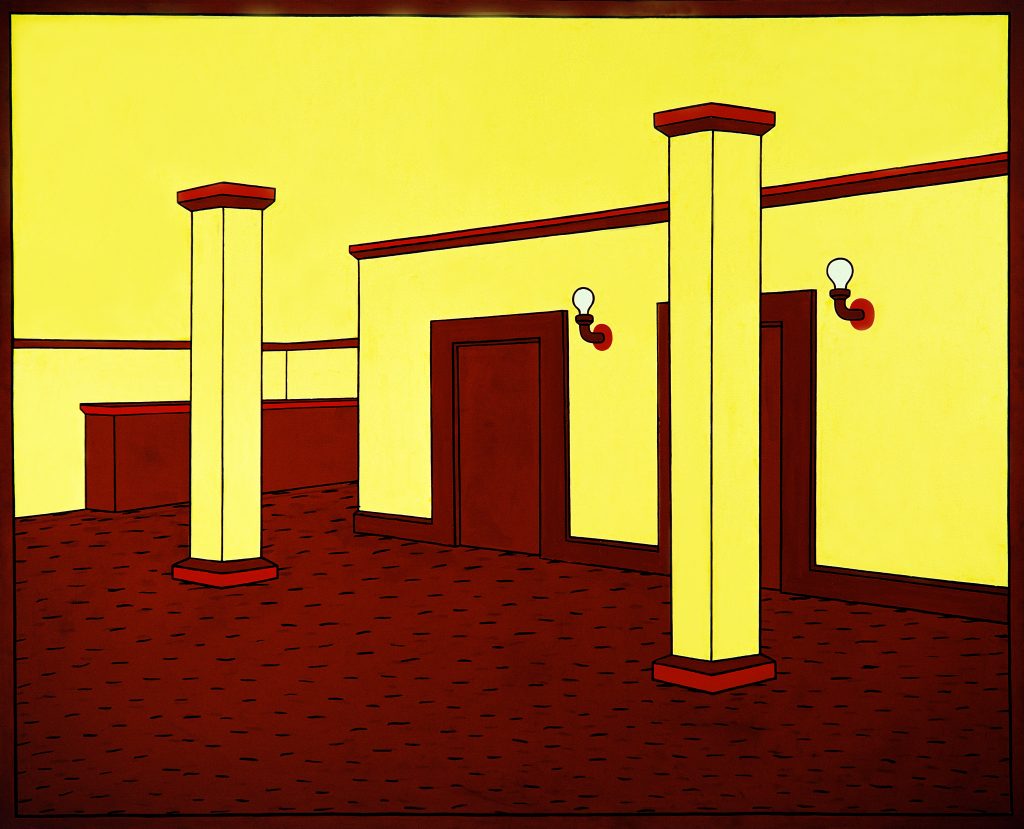

Looking at this exhibition one thing that became evident is just how much distance and time has passed since many of the artworks were first created. The 1950s post–war boom of Melbourne was 75 years ago and the population of Melbourne has gone from just over 1 million to 5.3 million. Melbourne has become more culturally diverse as well as much larger physically with new neighbourhoods stretching in every direction. At the same time our lives have been transformed in the digital age. It is a good opportunity for our visitors to reflect on some of the utopian and dystopian ideas about the growth of cities, and how these compare to their contemporary realities. For example, John Brack’s painting Subdivision, 1954, depicts the drone of outer city developments, devoid of trees. Melinda Harper’s Untitled, 2002, captures the colours of consumer and pop culture in an abstract painting that pulsates with energy and dynamism. Jan Senbergs’ Port Yard, 1981, depicts the eerie nature of the industrial architecture of a working port. Dale Hickey captures the interior of a theatre, Foyer Bercy Theatre, 1978, which has long gone from central Melbourne. Louise Hearman captures haunting nights in her dream–like paintings from 1997 and 2003, while Sidney Nolan captures the joy of swimming in Divers, Swimmers, c 1945.

Dale Hickey, Untitled (Studio series) 2004, TarraWarra Museum of Art Collection. Gift of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AO. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program 2009

*****

Are you a teacher or educator? Join our Learning & Engagement mailing list to get occasional updates from our team about school tours, education resources, personal development sessions and other education updates.