Hoda Ashfar and Elyas Alavi: Persian (Farsi) translation

Learn more about TarraWarra Biennial 2023 artworks by Hoda Ashfar and Elyas Alavi

These artworks were exhibited during the TarraWarra Biennial 2023: ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili, curated by Dr Léuli Eshrāghi.

Learn more about the TarraWarra Biennial 2023 artists Elyas Alavi and Hoda Afshar

Elyas Alavi

Hazara artist and poet Elyas Alavi’s work Cheshme-e jaan چشمه ِ جان (The Spirit Spring), 2023, comprises neon phrases, photographic collages, wooden rehal (book rests) made with repurposed railway sleepers, from some of the differing gauges no longer used on lines spanning Australia’s south to north between Tarndanya (central Adelaide) and Garramilla (Darwin). These same railways were connected to important camel lines running 1000 miles in various directions established by well-organised South Asian cameleers from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Kashmir, Pakistan and India. Elyas has drilled small holes in the timber to mark each rehal with Hazara motifs connected to ancestral villages and valleys across central Afghanistan. The vivid blue neon phrases that sit atop the rehal were first penned by the great Persian poet Mawlānā from Balkh, also known as Rumi.

جان من از جان تو چیزی شنود

چون دلم از چشمه تو آب خورد

My soul heard something from yours

Since my heart drank from your spring

Quoted in this context, they align Elyas’s installation with the continuing visual language of Islamic design, architecture, and adornment from a time when Persian/Dari, Urdu/Hindi, Bengali, Baluch, Pashto, Adnyamathanha, Arabunna, Wangkangurru, Warumangu, and other First Nations languages were commonly spoken.

Displayed on an adjacent wall, a series of photographic collages bearing witness to storied places across Central Australia are held together with partial letters of the Persian/Dari alphabet; fragments of memory and connection. Here Elyas alludes to the injustices that the Cameleers were subject to under the White Australia Policy whereby, despite their considerable contributions towards the colonial project, Cameleers were considered cheap labour, widely vilified by settler colonial governments and media, only granted temporary visas, prohibited from marrying or bringing their families, and refused citizenship. As Elyas poignantly affirms, to this day thousands of peoples from the same region as the Cameleers face similar discrimination due to the impacts of Western imperialism, with thousands surviving in administrative limbo for more than ten years; an enduring legacy of the White Australia policy.

Applying his embodied lens as a former refugee to the circumstances of broader displacement of Indigenous and minoritised peoples of Central Asia, Elyas reveals the marked similarities in the historical treatment and contemporary experience of Hazara people in both Afghanistan and Australia.

Hoda Afshar

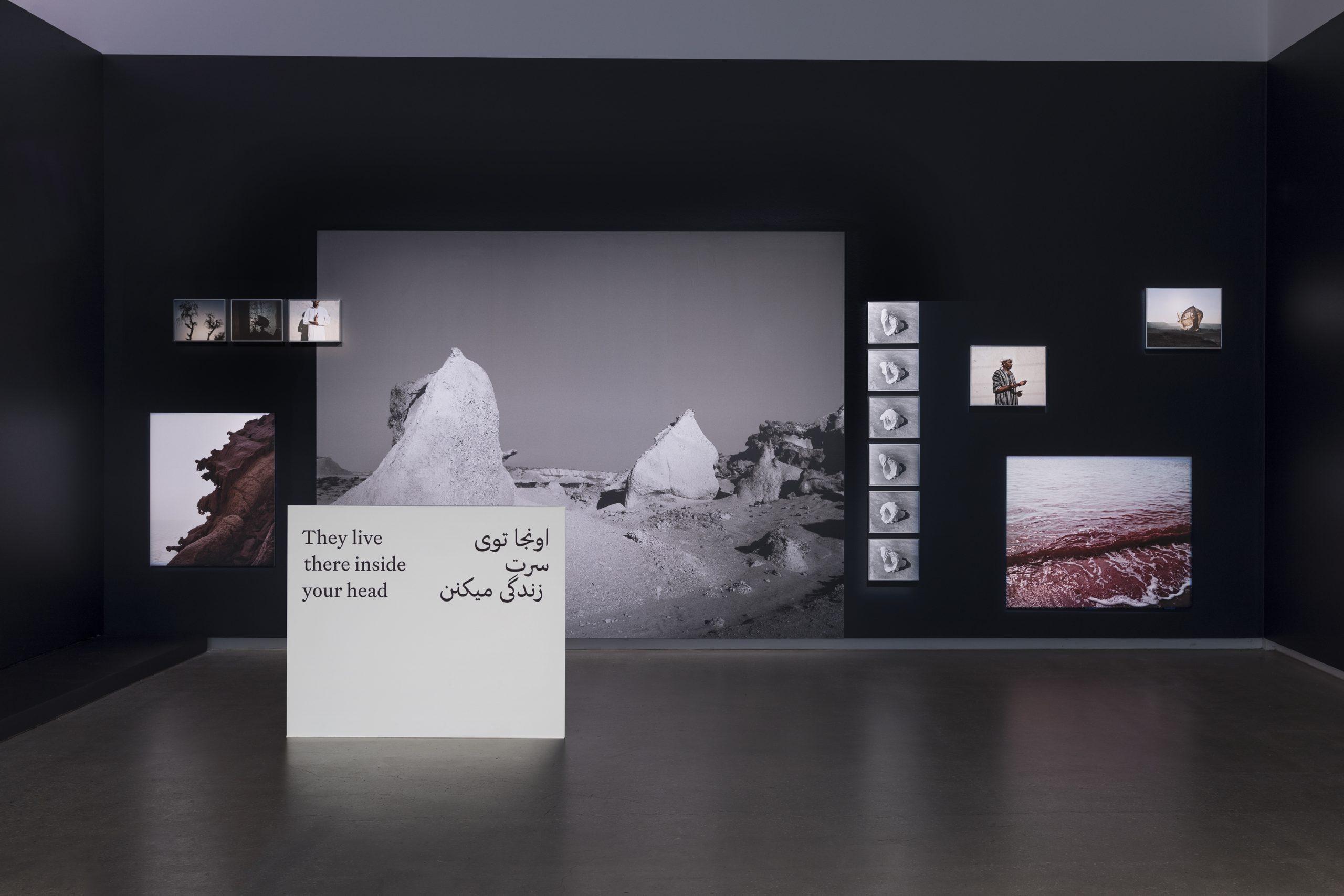

Invested in capturing intangible cultural memory and commenting on the accumulation of power both spiritual and political, artist and educator Dr Hoda Afshar presents a multi-layered wall assemblage from the Speak the Wind series, 2015–21. Emerging from her time in the islands of the Strait of Hormuz where she has travelled for years both before and since living in Australia, the installation comprises of images of veneration by local collaborators, fabric moving in the winds, poetic or religious inscriptions in Persian language, a crimson tide coming into shore, and large natural sand/rock formations in the dry environment of these islands.

The series, and this installation in particular, offers a portrait of the possessing wind and the physical experience of being possessed, which is often associated with these storied places. For Hoda, this honouring of the spiritual protection practices of the deeply cosmopolitan communities result from ‘many centuries of cultural and economic exchange, the traces of which are seen not only in the material culture of these islands but also in the customs and beliefs of their inhabitants’.

The abolition of slavery in Persia, which only occurred in 1929, created a deep structural racism against Afrodescendant peoples of contemporary southern Iran and neighbouring countries. That the spiritual world of African diasporic communities has prevailed, despite the fall and rise of absolute monarchist, democratic nationalist, and republican Islamic regimes in Iran, is testament to their tenacity. Echoing reverence for winds of differing character spanning this planet, local beliefs and ritual practices uphold a safe distance between human beings and winds who ‘may possess a person, causing her to experience illness or disease.’ To placate the winds harmful effects and negotiate its departure, a hereditary spiritual leader combines incense, music, and movement to communicate with the winds through the afflicted person in the language most linked to the elemental force. The striking sands, soils, sunlight, fabrics, skins, and spiritual gestures in Hoda’s imagery make evident a significant long-term relationship of careful navigation of these storied places and winds.

*****

The TarraWarra Biennial, 1 April–16 July 2023, featured newly commissioned works by 15 artists/artist groups focused on the interconnectedness of the peoples of Australia, Asia and the Great Ocean.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.